Technology

Hong Kong researchers create AI tool for detecting cardiovascular recurrence risk

A University of Hong Kong study using an AI-driven risk prediction model has found that patients with “three highs” have a 70 per cent chance of developing cardiovascular disorders again in 10 years.

The research team said on Friday that the finding not only underscored the importance for those patients to monitor their cardiovascular health, but also the potential of the AI tool to help with personalised treatment and allocating healthcare resources more efficiently.

The “three highs” – high blood pressure, high blood sugar and high blood lipids – affect 30, 10, and 50 per cent of Hong Kong residents aged between 18 and 84, respectively, according to the Department of Health.

These three metabolic conditions can raise the risk of heart, brain and blood vessel problems such as stroke and coronary heart disease, which have claimed more than 7,000 lives in Hong Kong in 2023.

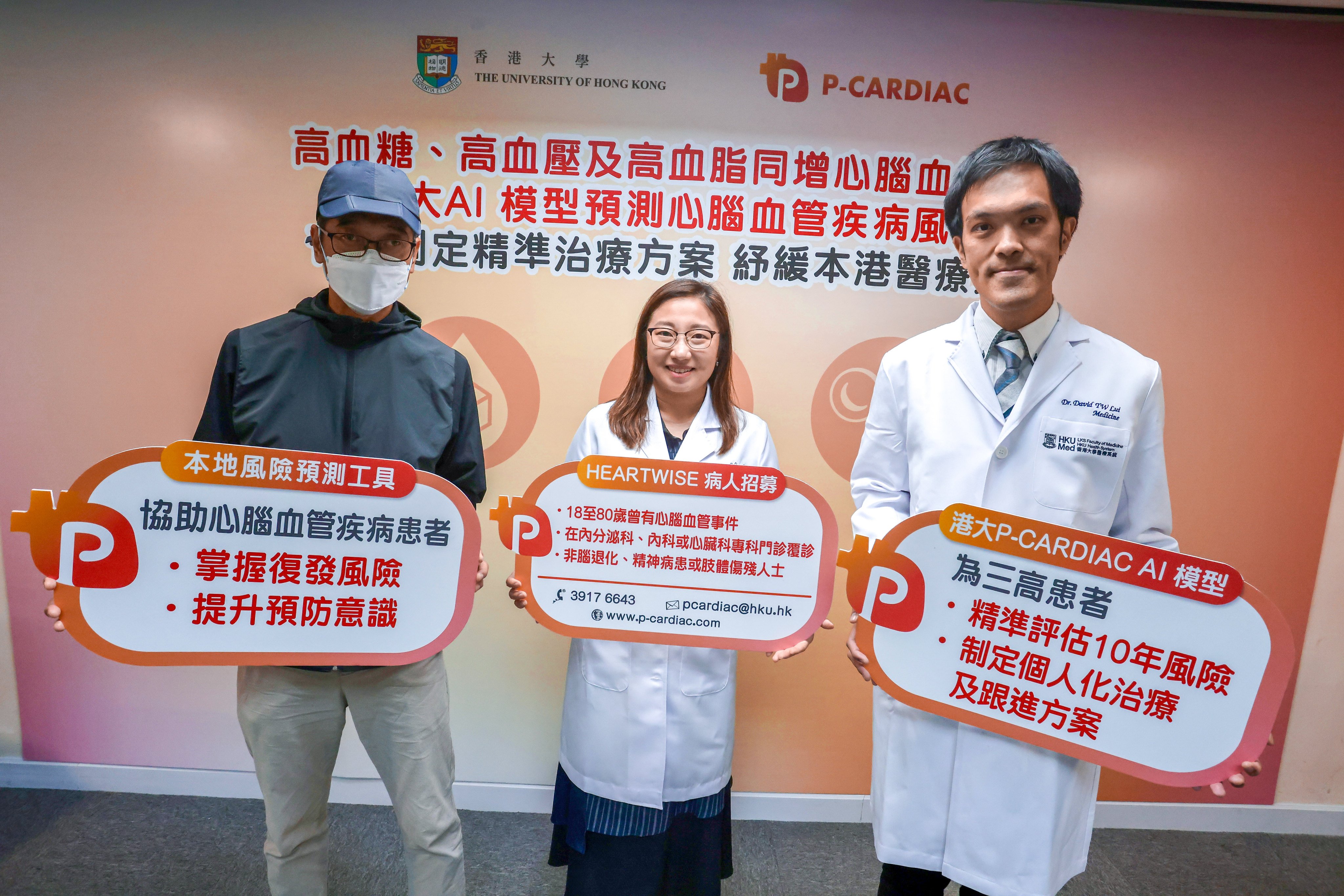

Celine Chui Sze-ling, assistant professor of HKU’s nursing school, said the university started developing P-CARDIAC, the first AI-driven risk assessment model based on the Chinese population, in 2019 to facilitate risk communication.

Chui said existing risk assessment tools used by frontline clinicians were developed decades ago, based on Western populations, covering only 20 risk variables.

P-CARDIAC was based on 13 million electronic medical records of 50,000 adult patients who underwent a blood lipid test at public hospitals and clinics in the Central and Western districts and Southern district between 2004 and 2019.

The model can auto-generate a personalised risk score to determine the likelihood of developing cardiovascular diseases in 10 years, based on more than 120 risk variables such as the patient’s age, gender, alcohol intake, cause of death, prescription history, and blood test results.

It can also visualise how big an impact different treatments will have on the risk score.

The accuracy of the assessment was 65 per cent, after being validated against about 260,000 cardiovascular disease patients from Kowloon and the New Territories.

“When the level of risk and the impact of treatment on the risk can be visualised, patients will be more motivated to follow doctors’ instructions,” Chui said.

Chui added that the accuracy of P-CARDIAC was well above Western models.

David Lui Tak-wai, clinical assistant professor of HKU’s department of medicine, said the model spares them the need to input the variables one by one in risk assessment tools.

“That can not only save our time in explaining the risk, but also help patients understand the importance of complying with doctors’ instructions and subsequently benefit doctor-patient relationships,” he said.

To provide more evidence for the wider adoption of P-CARDIAC, the team in 2024 recruited 1,200 patients with cardiovascular conditions in six public hospitals to test the model.

More than 90 per cent of them had at least one metabolic condition.

A P-CARDIAC analysis found the patients had a 70 per cent risk of developing cardiovascular diseases again in 10 years. The risk increases to 72 per cent if one has “three highs”, and 74 per cent with a stroke history.

The team is working to recruit about 2,000 more patients for the study.

In the long run, the tool could also facilitate more efficient use of overstretched healthcare resources by stratifying the risk faced by patients.

For example, those with a higher risk will have a shorter waiting time to see a doctor, while those with a lower risk can be seen by other professionals such as nurses and pharmacists, according to Chui.

She added that her team was working to apply the model in the clinical setting at both public and private sectors, hopefully within one or two years.

A University of Hong Kong study using an AI-driven risk prediction model has found that patients with “three highs” have a 70 per cent chance of developing cardiovascular disorders again in 10 years.

The research team said on Friday that the finding not only underscored the importance for those patients to monitor their cardiovascular health, but also the potential of the AI tool to help with personalised treatment and allocating healthcare resources more efficiently.

The “three highs” – high blood pressure, high blood sugar and high blood lipids – affect 30, 10, and 50 per cent of Hong Kong residents aged between 18 and 84, respectively, according to the Department of Health.

These three metabolic conditions can raise the risk of heart, brain and blood vessel problems such as stroke and coronary heart disease, which have claimed more than 7,000 lives in Hong Kong in 2023.

Celine Chui Sze-ling, assistant professor of HKU’s nursing school, said the university started developing P-CARDIAC, the first AI-driven risk assessment model based on the Chinese population, in 2019 to facilitate risk communication.

Chui said existing risk assessment tools used by frontline clinicians were developed decades ago, based on Western populations, covering only 20 risk variables.

P-CARDIAC was based on 13 million electronic medical records of 50,000 adult patients who underwent a blood lipid test at public hospitals and clinics in the Central and Western districts and Southern district between 2004 and 2019.

The model can auto-generate a personalised risk score to determine the likelihood of developing cardiovascular diseases in 10 years, based on more than 120 risk variables such as the patient’s age, gender, alcohol intake, cause of death, prescription history, and blood test results.

It can also visualise how big an impact different treatments will have on the risk score.

The accuracy of the assessment was 65 per cent, after being validated against about 260,000 cardiovascular disease patients from Kowloon and the New Territories.

“When the level of risk and the impact of treatment on the risk can be visualised, patients will be more motivated to follow doctors’ instructions,” Chui said.

Chui added that the accuracy of P-CARDIAC was well above Western models.

David Lui Tak-wai, clinical assistant professor of HKU’s department of medicine, said the model spares them the need to input the variables one by one in risk assessment tools.

“That can not only save our time in explaining the risk, but also help patients understand the importance of complying with doctors’ instructions and subsequently benefit doctor-patient relationships,” he said.

To provide more evidence for the wider adoption of P-CARDIAC, the team in 2024 recruited 1,200 patients with cardiovascular conditions in six public hospitals to test the model.

More than 90 per cent of them had at least one metabolic condition.

A P-CARDIAC analysis found the patients had a 70 per cent risk of developing cardiovascular diseases again in 10 years. The risk increases to 72 per cent if one has “three highs”, and 74 per cent with a stroke history.

The team is working to recruit about 2,000 more patients for the study.

In the long run, the tool could also facilitate more efficient use of overstretched healthcare resources by stratifying the risk faced by patients.

For example, those with a higher risk will have a shorter waiting time to see a doctor, while those with a lower risk can be seen by other professionals such as nurses and pharmacists, according to Chui.

She added that her team was working to apply the model in the clinical setting at both public and private sectors, hopefully within one or two years.